| GLENN A. WRIGHT, |

|

Jerry N. Jones, Assistant United States Attorney, (William J. Leone, United States Attorney, with him on the brief), Office of the United States Attorney for the District of Colorado, Denver, Colorado, appearing for Appellees.

Mary Price, Esq., General Counsel, Families Against Mandatory Minimums, Denver, Colorado, and Philip A. Cherner, Esq., Law Office Of Philip A. Cherner,

Washington, DC, for Amicus Curiae for Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

This appeal presents a straightforward case of statutory interpretation. The statute at issue, 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b), allows a prisoner to earn credit toward the service of his sentence for exemplary conduct in prison. The provision provides in relevant part:

[A] prisoner who is serving a term of imprisonment of more than 1 year other than a term of imprisonment for the duration of the prisoner's life, may receive credit toward the service of the prisoner's sentence, beyond the time served, of up to 54 days at the end of each year of the prisoner's term of imprisonment, beginning at the end of the first year of the term, subject to determination by the Bureau of Prisons that, during that year, the prisoner has displayed exemplary compliance with institutional disciplinary regulations. . . . [C]redit for the last year or portion of a year of the term of imprisonment shall be prorated and credited within the last six weeks of the sentence.

18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1) (emphasis added). The BOP issued a regulation, after notice and comment, see 5 U.S.C. § 553, interpreting the emphasized portion of the statute. The regulation provides that the BOP will "award 54 days credit toward service of sentence . . . for each year served." 28 C.F.R. § 523.20(a) (emphasis added). The BOP has also issued, as part of its Sentence Computation Manual, Program Statement 5880.28, which provides a formula for calculating good-time credit on sentences exceeding a year and a day. As the Seventh Circuit has explained:

[The] formula is based on the premise that for every day a prisoner serves on good behavior, he may receive a certain amount of credit toward the service of his sentence, up to a total of fifty-four days for each full year. Thus, under the Bureau's formula, a prisoner earns .148 days' credit for each day served on good behavior (54 / 365 = .148), and for ease of administration the credit is awarded only in whole day amounts. Recognizing that most sentences will end in a partial year, the Bureau's formula provides that the maximum available credit for that partial year must be such that the number of days actually served will entitle the prisoner (on the .148-per-day basis) to a credit that when added to the time served equals the time remaining on the sentence.

White v. Scibana, 390 F.3d 997, 1000 (7th Cir. 2004), cert denied, White v. Hobart, --- U.S. ---, 125 S. Ct. 2921, 2922 (2005). In other words, the BOP reads the statute as mandating good time credits to be calculated based on the amount of time served in prison.

Mr. Wright argues, however, that § 3624(b)(1) unambiguously requires good time credit to be calculated based upon the sentence imposed, as opposed to the time served. Therefore, according to Mr. Wright, he is entitled to fifty-four days of good-time credit for each of the fourteen years to which he was sentenced, minus any deductions for disciplinary violations.

II.

Because this case involves an administrative agency's construction of a statute, our analysis is governed by Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984). Under Chevron, we first determine "whether Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue." Id. at 842. If so, our inquiry is at an end; "the court 'must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress.'" Food and Drug Admin. v. Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., 529 U.S. 120, 132 (2000) (quoting Chevron, 467 U.S. at 843). If, on the other hand, the statute is silent or ambiguous on the issue, we will determine whether the agency's view is based on a permissible construction of the statute. Chevron, 467 U.S. at 843.

We review issues of statutory construction de novo. Robbins v. Chronister, 435 F.3d 1238, 1240 (10th Cir. 2006) (en banc). "'[O]ur task is to interpret the words of the statute in light of the purposes Congress sought to serve.'" Hain v. Mullin, 436 F.3d 1168, 1176 (10th Cir. 2006) (en banc) (quoting Dickerson v. New Banner Inst., Inc., 460 U.S. 103, 118 (1983)). Our starting point, as always, is the language employed by Congress. Id. We read the words of the statute "in their context and with a view to their place in the overall statutory scheme." Brown & Williamson, 529 U.S. at 132-133; Hain, 436 F.3d at 1177.

Our focus in this case is directed at the meaning of "term of imprisonment." The phrase has inconsistent meanings throughout § 3624. For example, § 3624(a) states that "[a] prisoner shall be released by the [BOP] on the date of the expiration of the prisoner's term of imprisonment, less any time credited toward the service of the prisoner's sentence as provided in subsection (b)." Here, "term of imprisonment" plainly refers to the "sentence imposed" since the BOP is instructed to deduct time credited from the prisoner's sentence. Perez-Olivo v. Chavez, 394 F.3d 45, 49 (1st Cir. 2005). In § 3624(d), however, the same phrase means "time served." That section provides that "[u]pon the release of a prisoner on the expiration of the prisoner's term of imprisonment, the [BOP] shall furnish the prisoner with [suitable clothing, an amount of money not to exceed $500, and transportation]." 18 U.S.C. § 3624(d). Indeed, "[i]t would make no sense to provide [a prisoner] these amenities at a time when the prisoner's original imposed sentence had expired--a date that would obviously occur after the prisoner had been released based on good time credits." Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 49 (quoting Loeffler v. Bureau of Prisons, No. 04-4627, 2004 WL 2417805, at *3 (S.D.N.Y. Oct. 29, 2004)).

The phrase is also used three times in the first sentence of § 3624(b)(1). The provision applies to a prisoner "serving a term of imprisonment of more than 1 year other than a term of imprisonment for the duration of the prisoner's life." 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1) (emphasis added). Here, the phrase means "sentence imposed" since the statute only applies to prisoners who have been sentenced to more than one year's imprisonment and less than life. Yi v. Fed. Bureau of Prisons, 412 F.3d 526, 531 (4th Cir. 2005). The BOP must be able to determine, on the first day the prisoner arrives in prison, if he will be eligible for good time credits. If, on the other hand, the phrase meant "time served" then a prisoner "who initially would be eligible for the credit because his sentence was, say, 366 days, would become ineligible once the credit was taken into account." White, 390 F.3d at 1001.

But the specific use of the phrase at issue here describes not how to determine whether a prisoner is eligible for good time credits, but how (and when) to calculate them. At the end of each year of imprisonment, if the BOP determines that the prisoner's behavior during that year was exemplary, then it may award up to fifty-four days credit toward service of the prisoner's sentence. 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1). The statute contemplates retrospective annual assessment of a prisoner's behavior--that is, Congress intended that prisoners earn good time credits by "display[ing] exemplary compliance with institutional disciplinary regulations." 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1). To interpret "term of imprisonment" to mean "sentence imposed," as Mr. Wright suggests, an inmate could receive credit for time when he was not in prison at all. See White, 390 F.3d at 1002. For example, Mr. Wright suggests that he is entitled to fifty-four days of credit for each of the fourteen years to which he was sentenced (minus any deductions for less-than-exemplary behavior), even though it is undisputed that Mr. Wright will not serve any of his fourteenth year. Simply put, "[a]n inmate who is not in prison cannot 'earn' credit for compliance with disciplinary regulations," Yi, 412 F.3d at 532, and Mr. Wright's reading of the statute would appear to frustrate Congress's intent, see Sash v. Zenk, 428 F.3d 132, 137 (2d Cir. 2005) (stating that such a reading would "conflict with § 3624's directive that good time be calculated at the end of each year" based on the prisoner's actual behavior during that year).

Mr. Wright next argues that his reading is bolstered by the use of the word "credit" in § 3624(b)(1). He suggests that "credit" means "deduction from an amount otherwise due" and can only refer to the sentence imposed since it is impossible to get "credit" for time served, because that time is no longer due. We agree with Mr. Wright that a prisoner receives "credit" toward his sentence imposed. Indeed, the statute explicitly says as much: a prisoner "may receive credit toward the service of the prisoner's sentence." 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1). We disagree, however, with Mr. Wright's conclusion that this renders the use of the phrase "term of imprisonment" to unambiguously mean "sentence imposed."

Nor does legislative history resolve this dispute. See Anderson v. U.S. Dept. of Labor, 422 F.3d 1155, 118081 (10th Cir. 2005) (ordinary tools of statutory construction include consultation of legislative history). Although earlier good time credit statutes revealed a clear Congressional intent to calculate credits based on the sentence imposed, see, e.g., 18 U.S.C. § 4161 (repealed 1984), the legislative history of the current statute does not indicate any Congressional intent to calculate credits based on the sentence imposed as opposed to the time served. Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 50. Nor do some congresspersons' general statements made shortly after the passage of the statute evidence a clear congressional intent to calculate credits based on the sentence imposed. See, e.g., 131 Cong. Rec. E37-02 (Jan 3, 1985) (Statement of Rep. Lee Hamilton) ("Now sentences will be reduced only 15% for good behavior"); see also Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 51 (stating that the general statements do not resolve ambiguity in the phrase "term of imprisonment").

Nevertheless, Mr. Wright argues that there is a presumption that identical words appearing in different parts of the same statute have the same meaning and that the presumption is strongest when a term is repeated in a single sentence. See Brown v. Gardner, 513 U.S. 115, 118 (1994). The rule of consistency, as Mr. Wright acknowledges, is only a presumption. "[T]he presumption is not rigid and readily yields whenever there is such variation in the connection in which the words are used as reasonably to warrant the conclusion that they were employed . . . with different intent." Gen. Dynamics Land Sys., Inc. v. Cline, 540 U.S. 581, 595 (2004). Indeed, as discussed above, the phrase means different things in § 3624(a) (sentence imposed) and § 3624(d) (time served). As for the issue at hand, we hold, in accordance with nearly every circuit court to consider the issue, that "term of imprisonment" is ambiguous as it is susceptible to more than one interpretation. See Bernitt v. Martinez, 432 F.3d 868, 869 (8th Cir. 2005); Sash, 428 F.3d at 136; Petty v. Stine, 424 F.3d 509, 510 (6th Cir. 2005); Brown v. McFadden, 416 F.3d 1271, 127273 (11th Cir. 2005); Yi, 412 F.3d at 533; O'Donald v. Johns, 402 F.3d 172, 174 (3d Cir. 2005); Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 52; White, 390 F.3d at 100203; Pacheco-Camacho v. Hood, 272 F.3d 1266, 126970 (9th Cir. 2001); but see Moreland v. Fed. Bureau of Prisons, 431 F.3d 180, 186 (5th Cir. 2005) (holding that § 3624(b)(1) unambiguously directs good time credits to be calculated at the end of each year of time served).

Before proceeding to the second step of our Chevron analysis, we briefly digress to resolve an intermediate argument raised by Mr. Wright. Mr. Wright contends that Chevron deference is inappropriate in this case because if a sentencing statute is ambiguous, we must apply the rule of lenity to construe the ambiguity in his favor. United States v. Bass, 404 U.S. 336, 347 (1971) (stating that "ambiguity concerning the ambit of criminal statutes should be resolved in favor of lenity"). Indeed, the rule of lenity applies "not only to interpretations of the substantive ambit of criminal prohibitions, but also to the penalties they impose." Bifulco v. United States, 447 U.S. 381, 387 (1980). The principle of lenity is founded on two firmly-rooted ideas in this country's tradition: "First, a fair warning should be given to the world in language that the common world will understand, of what the law intends to do if a certain line is passed. . . . Second . . . legislatures and not courts should define criminal activity." Bass, 404 U.S. at 348 (internal quotations and citations omitted).

We conclude that the rule of lenity does not apply here. Section 3624(b) is neither a substantive criminal statute nor does it prescribe the punishment imposed for a violation of such a statute. Sentencing credits are awarded to those prisoners who behave in prison--they "are awarded to ensure administrative order in prisons, not to further the punitive goals of the criminal law." Sash, 428 F.3d at 13435. Further, neither of the rule's underlying principles are implicated here. As an administrative tool, rather than a punitive measure, the ambiguity of § 3624(b) "does not result in any lack of notice to potential violators of the law of the scope of the punishment that awaits them." Sash, 428 F.3d at 134. Moreover, because § 3624(b) is not criminal in nature, neither the courts nor the BOP have infringed upon the role of the legislature to define what constitutes criminal activity and how it should be punished. Id. at 135.

Having concluded that the statute is ambiguous, and that the rule of lenity does not apply, the next step in the Chevron analysis is to determine whether the BOP's interpretation of the statute is a permissible one. Chevron, 467 U.S. at 843.(1) As the preceding discussion shows, the BOP's interpretation of § 3624(b)(1) is clearly a reasonable one. The statute directs that a prisoner "may receive credit toward the service of the prisoner's sentence . . . at the end of each year." 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1). "This is a clear congressional directive that the BOP look retroactively at a prisoner's conduct over the prior year, which makes it reasonable for the BOP only to award [good time credits] for time served." Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 53. Indeed, every circuit to consider the issue has also concluded that such an interpretation is reasonable. See Bernitt, 432 F.3d at 869; Sash, 428 F.3d at 136; Petty, 424 F.3d at 510; Brown, 416 F.3d at 127273; Yi, 412 F.3d at 534; O'Donald, 402 F.3d at 174; Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 53; White, 390 F.3d at 1003; Pacheco-Camacho, 272 F.3d at 1270. III.

For the reasons set forth above, the District Court's order dismissing Mr. Wright's petition for a writ of habeas corpus is AFFIRMED.

05-1383, Wright v. Federal Bureau of Prisons

O'BRIEN, J. concurring.

I concur in the result reached by the majority. If the statutory language were ambiguous, I would join in the majority's reasoning and discussion affording Chevron deference to the agency's interpretation of the statute. But, like the Fifth Circuit, I think the statute unambiguously specifies the method by which good time is to be calculated. Moreland v. Federal Bureau of Prisons, 431 F.3d 180, 186 (5th Cir. 2005). The Bureau of Prisons has been faithful to that method.

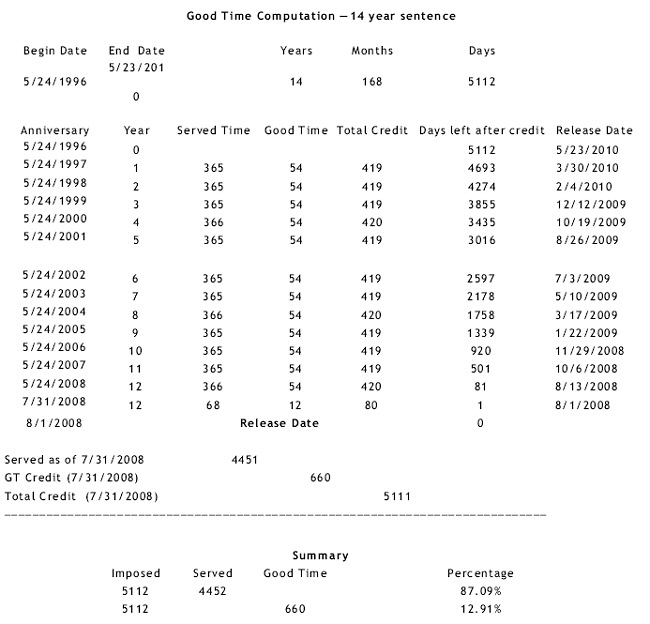

Wright's term of imprisonment is 168 months; that is also 14 years or 5112 days. It commenced May 24, 1996. Wright may legitimately ask, "When do I get out?" Absent good time credits the answer is quite simple. Each day Wright serves reduces the remaining days by one. It is (or can be) calculated and credited daily. Provisions for good time credit add a wrinkle and prompt other questions.

With respect to good time credit Wright may ask, "How much good time credit do I get, when is it to be credited and how is it to be credited?" The statute answers each question with straight-forward language.(1)

First, the amount is unambiguous, because it is easy to calculate. It depends upon the prisoner's conduct but "cannot exceed 54 days per year."

Second, when it is to be credited is also unambiguous and the calculations are, again, simple. It is to be credited "at the end of each year of the prisoner's term of imprisonment, beginning at the end of the first year of the term," the sentence anniversary date. A term of imprisonment expressed in months must be converted into years in order to determine anniversary dates; for a fourteen year sentence with no good time credits, there are 13.(2) The credit is to be applied annually on the anniversary date.

Finally, how the credit is to be applied seems to be equally clear and the

calculations equally simple. Good time credit is to applied "toward the service of

the prisoner's sentence." A prisoner serves his sentence day by day. He expects

to, and does, receive credit against the "term of imprisonment" for each day he

has served. Thus, to calculate the time remaining in a "term of imprisonment"

the imposed term must be converted to days. A 168 month sentence beginning

May 24, 1996, ends May 23, 2010. That is 5112 days, including the extra days in

leap years. Each day served is deducted from the total days to be served. At the

end of the first year the prisoner has 4747 days remaining (5112-365 = 4747). If

the prisoner earned maximum good time during that year it must be credited on

the sentence anniversary date. Using the method for crediting time actually

served (deducting it from the time remaining) the prisoner would then have 4693

days remaining in his "term of imprisonment" (4747-54 = 4693). The

calculations continue, granting daily credit for time actually served and annual

credit for good time earned, until the days remaining equal zero. Following is a

spread sheet example (faithful to statutory language) of a 14 year sentence with

maximum good time credits. It is intended for illustrative purposes only and does

not purport to be the Bureau of Prisons' actual calculation here.

Wright proposes a method for crediting good time at odds with the practices of the Bureau of Prisons. It is most clearly stated in the Brief of Amicus Curiae, which Wright explicitly adopted at oral argument:

Petitioner and Amicus, . . . read the statute literally to grant a "credit," that is a deduction, at the "end of each year" of the "term of imprisonment" imposed, if "during that year," the prisoner has been well behaved. 18 U.S.C. § 3624(b). Accordingly, after the prisoner has served a year, the Bureau may apply a "credit," by definition a "deduction," of up to 54 days from that year, if, "during that year," the prisoner was well behaved. This credit, applied to the prior year of the term, establishes the day on which service of that year was fully satisfied. If the prisoner is granted 54 days' credit, he satisfied service of the first year of the term of imprisonment on the 311th day actually served. The 312th day served thus becomes the first day of the second year of the term. After another year of the term has passed, the Bureau must again look back and consider the prisoner's conduct during the preceding year and again make the appropriate deduction, which establishes the date on which service of that year was satisfied and the succeeding year begins, and so on. Honoring the exact wording of the statute, then, a prisoner will be eligible for 54 days for each year of the "term of imprisonment" imposed by the sentencing court. The plain words of the statute are thus effectuated without the need to read the phrase "term of imprisonment" to have two different meanings the "term imposed" and the "time served" in the single sentence in which it appears, as the Bureau of Prisons does.

Amicus Br., Families Against Mandatory Minimums, at 2-3.

A good lawyer can formulate an argument that makes a hash of almost any statutory, regulatory or contractual language.(3) We must look through the argument. Our approach is practical and circumspect. "As in all statutory construction cases, we begin with the language of the statute." Barnhart v. Sigmon Coal Co., 534 U.S. 438, 450 (2002). If the statutory language is not ambiguous, and "the statutory scheme is coherent and consistent," further inquiry is unneeded. Id. (quotation marks omitted). "The plainness or ambiguity of statutory language is determined by reference to the language itself, the specific context in which that language is used, and the broader context of the statute as a whole." Robinson v. Shell Oil Co., 519 U.S. 337, 341 (1997); see also U.S. Nat'l Bank of Or. v. Indep. Ins. Agents of Am., Inc., 508 U.S. 439, 455 (1993) ("Statutory construction is a holistic endeavor, and, at a minimum, must account for a statute's full text, language as well as punctuation, structure, and subject matter.") (internal quotation and citation omitted).

Wright's arguments present a possible, but implausible, gloss on unambiguous statutory language. If we can fairly do so, we should avoid, not beget, a construction of a statute making it ambiguous.

1.Congress has implicitly delegated interpretative authority over this issue to the BOP. Perez-Olivo, 394 F.3d at 52; Pacheco-Camacho, 272 F.3d at 1270. Accordingly, the BOP's interpretation of the statute is afforded full Chevron deference and we "may not substitute [our] own construction of a statutory provision for a reasonable interpretation made by the administrator of an agency." Chevron, 467 U.S. at 844; Harbert v. Healthcare Servs. Group, Inc., 391 F.3d 1140, 1147 (10th Cir. 2004)

1.18 U.S.C. § 3624(b)(1) provides in relevant part:

[A] prisoner who is serving a term of imprisonment of more than 1 year other than a term of imprisonment for the duration of the prisoner's life, may receive credit toward the service of the prisoner's sentence, beyond the time served, of up to 54 days at the end of each year of the prisoner's term of imprisonment, beginning at the end of the first year of the term, subject to determination by the Bureau of Prisons that, during that year, the prisoner has displayed exemplary compliance with institutional disciplinary regulations.. . . [C]redit for the last year or portion of a year of the term of imprisonment shall be prorated and credited within the last six weeks of the sentence.

2. All other things being equal, the 14th anniversary would be the release date.

3. Years ago Chief Justice Burger gave a speech lamenting the poor courtroom competence of many lawyers. With tongue firmly in cheek, Art Buchwald penned a retort as only he could, or would. Among other things he said: "A competent, first class lawyer can tie a case up in knots not only for the jury but for the judge as well. . . . It is the able lawyers [not the incompetent ones] who should not be permitted in the courtroom since they are the ones who are doing all the damage." See, Art Buchwald, "Bad Lawyers Are Very Good for the U.S. Justice System," 64 A.B.A. J. 328 (1978).

"An incompetent lawyer can delay a trial for months or years. A competent lawyer can delay one even longer." Evelle Younger.